Vive la France! - "Les Miserables" and the French Revolution

- lillithpatzer

- Oct 16, 2024

- 7 min read

Paris, 6. June. 1832

In the narrow streets around Rue St. Martin, about 500 men have barricaded themselves. On this day, the usually bustling street of Paris smells of gunpowder and blood. The shutters of the surrounding houses remain closed despite the muggy heat. They huddle next to the dead bodies of their comrades, the hope for help seems lost. It is four o'clock, and it is raining heavily.

In the following hours, the thunder of cannons will not cease. Just a few hours ago, they fought with hunger for victory; considering the sheer number of their opponents—estimated at about 60,000 men at that time—they are left with only the option to die heroically.

By this time tomorrow, they will be utterly defeated.

In a week, tumultuous daily life will return to Rue St. Martin.

In a decade, the courage of the patriots will give their successors the backbone to continue the fight for liberty, equality, and fraternity.

In two centuries, people will only read about it.

Heinrich Heine, who is staying just two streets away in Porte St. Denis and documenting the events of the June Uprising on-site, cannot sleep that evening.

A similar scene is described by Victor Hugo, who has a great personal interest in the French Revolution, a few years later in his world-renowned novel "Les Misérables." However, Hugo's story begins a few years earlier with a man named Jean Valjean.

Jean Valjean

In recent years, Valjean has been referred to solely as "24601," as he was sentenced to 19 years of hard labor in a so-called "Bagno," where prisoners, usually chained together in pairs, had to perform the most arduous and dangerous work in shipbuilding.

Valjean has just completed his sentence when we first encounter him. Upon leaving the penitentiary, the police director Javert, another central figure in the story, gives him a "yellow pass." This pass identifies Valjean as a dangerous criminal, making it nearly impossible for him to find honest employment. It’s important to consider that we are in early 19th-century France, where industrialization was on the rise, leading to a lack of jobs and widespread poverty.

Starving and destitute, Valjean encounters the kind-hearted Bishop Myriel in Digne, who offers him food and a place to stay for the night. The bishop is reportedly modeled after the real-life Bishop of Digne, François-Melchior-Charles-Bienvenu de Miollis, who was appointed to the position by Napoleon in 1805.

However, when morning comes and the birds begin to sing, Valjean has already fled—taking with him valuable loot from the bishop’s residence. His joy over this fine haul is short-lived, as he is soon discovered by the "gendarmes," or policemen, and is forcefully taken back to the bishop's house. To everyone's astonishment, the bishop assures the authorities that he gifted Valjean these possessions, prompting the guards to withdraw suspiciously.

Bishop Myriel even gifts Valjean two silver candlesticks, but not without setting a condition: Valjean must use the fine silver to become an "honest man." Deeply touched by the bishop's kindness, Valjean resolves to follow God's path and adhere to the bishop's condition.

Fantine

After a time jump of five years, we find ourselves in the year 1815 (17 years before the June uprising). Valjean has settled in the northern French town of "Montreuil-sur-Mer," also known as Montreuil by the sea (not to be confused with Montreuil (Seine-Saint-Denis), a suburb of Paris), under the alias "Madeleine." Through a series of good deeds, he has become well-liked and has even been appointed mayor.

In Montreuil, we meet another key character in our story: Fantine. The young woman works as a grisette in one of Madeleine's (Valjean's) factories.

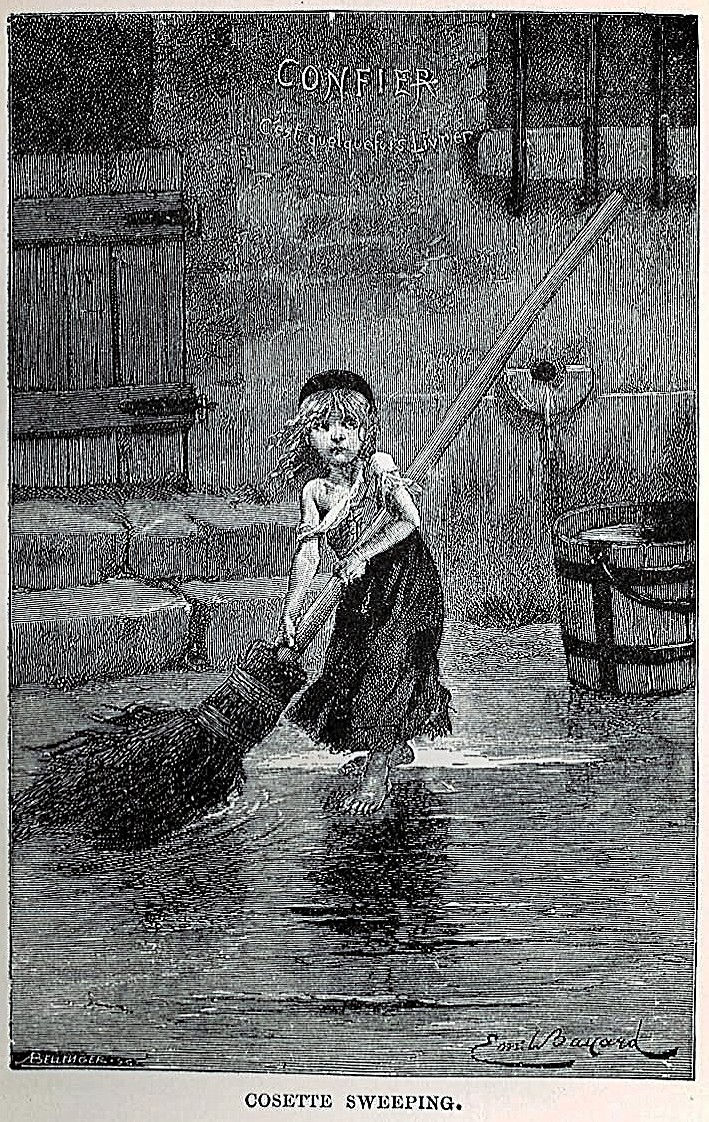

"Grisette" was a term used for a single young woman who lived independently of her parents and earned her own income, which was quite unusual for that time. However, Fantine has little to manage, as she sends every sou (the equivalent of a cent) she earns to the foster family of her daughter, Cosette, the Thénardiers. The father of the child, a student named Félix Tholomyès, has abandoned her with the child. Soon enough, the townspeople of Montreuil discover that Fantine has an illegitimate child, leading to her losing both her job and social standing.

To continue providing for Cosette, Fantine first sells her blonde hair, then her teeth, and finally herself. When she is attacked by a “client” during her nightly business, she fights back but is arrested by Inspector Javert. During her hearing, however, Madeleine intervenes, believing Fantine's story. Although Fantine has pneumonia, the hospital sisters to whom Madeleine brings her, as well as his promise to soon bring her daughter Cosette to her, keep the young mother alive.

Meanwhile, Javert suspects an uninvolved man named Champmathieu is actually the escaped Valjean. He reports this suspicion to Mayor Madeleine (Valjean) and confesses that he previously suspected Madeleine himself, which he deeply regrets.

Valjean finds himself in a dilemma: Should he turn himself in to spare the innocent Champmathieu from punishment? After all, the responsibility for hundreds of factory workers and the town's residents rests on his shoulders, and he feels obligated to Fantine as well.

Ultimately, he recalls the words of Bishop Myriel; he wanted to be an honest citizen. Madeleine reveals himself as Valjean and is arrested at Fantine's bedside. As a result of the shock—something she never would have suspected of her savior—she dies.

But don’t worry; our story is not over yet. Valjean fakes his own death to escape imprisonment and protect his fortune. Next, he sets out to retrieve Cosette.

The promise to care for Cosette weighs heavily on his shoulders, yet he fully embraces his new role as a father. With a new identity—Fauchelevent—Valjean heads to Paris, where he engages in numerous charitable projects, making him a prominent figure there as well.

Cosette & Marius

Cosette grows up under the protective hand of her adoptive father in Rue Plumet. However, Valjean soon faces a greater threat than Javert, who is still on the trail of the escaped 24601—one that comes in the form of a suitor for his daughter. During walks in the Luxembourg Gardens, she catches the eye of a law student from a well-to-do family named Marius Pontmercy, who immediately falls in love with her.

Like many students of the time, he establishes connections to a revolutionary student movement, the Friends of the ABC, through a good friend. The name is not an honor for the French alphabet but rather a play on words: “a-b-c,” when said quickly, sounds like the French word "abaissé," which translates to "the oppressed."

To get closer to Cosette, Marius wants to find out where she lives. He turns to his good friend and neighbor Éponine Thénardier for help. Does the last name sound familiar? Éponine is the biological daughter of the Thénardiers, the couple who took in Cosette as a young girl. While Éponine was favored and spoiled as a child, her situation has changed. While Cosette lives a carefree life in the upper class, Éponine is forced to support her family’s criminal activities to avoid starving. Moreover, she is also in love with Marius, who remains oblivious to her feelings.

Nevertheless, she provides him with Cosette's address, prompting Marius to write a long letter expressing his romantic feelings for her.

But Marius is not the only one who learns Cosette's address: Éponine's father realizes that it is the home of the wealthy Monsieur Fauchelevent and devises a plan to rob both father and daughter. However, a familiar figure—Inspector Javert—intervenes and foils the robbery, unaware that the long-sought convict 24601 is right before him.

Yet Thénardier is not ready to give up. Valjean also fears for the secrecy of his identity, which leads him to decide to flee to England with Cosette.

The Miserables

Now events are escalating and bringing us quickly back to the beginning of our story—Marius sees no reason to live without Cosette by his side, which is why he participates in the June uprising alongside the Friends of the ABC. Éponine also mingles with the revolutionaries, disguised as a man.

Valjean, who is now aware of the relationship between his foster daughter and Marius, throws himself into the fray to bring Marius back to Cosette. Ultimately, Javert infiltrates the group as a double agent, planning to quash the revolt in its infancy.

However, he is quickly uncovered and immediately detained—there are plans to eliminate him as soon as possible. Valjean requests to handle this task himself. Javert finally recognizes his arch-enemy. The inspector is almost eager to be shot, as this would confirm his prejudices against criminals. He does not believe that a man who has once fallen afoul of the law can ever become an honorable man again. To his horror, Valjean secretly frees Inspector Javert. The latter is deeply shaken in his sense of justice and order. He cannot live with the knowledge of being in a criminal's debt, which is why he throws himself into the Seine.

Back at the barricades—several friends of the ABC have already fallen. However, the revolutionaries come up with a clever idea: they exchange their clothing with that of fallen National Guardsmen. This gives rise to the rumor that the National Guard has sided with the patriots, causing the latter to be indecisive for some time about which party to support.

By the end of this uprising, all the friends of the ABC are dead. Éponine has also sacrificed herself to protect Marius from a bullet. With the help of Valjean, who carries the unconscious Marius through the sewers of France, the young man survives. A happy life for the young couple seems to be in sight. Then Valjean shares his tragic past with Marius, causing the latter to distance himself—and thus also Cosette—from Valjean. At the wedding of the young couple, the Thénardiers sneak in. Through them, Marius realizes that it was Valjean who saved him at the barricades. He wants to ask Valjean, who has since retired to a monastery, for forgiveness. However, Valjean has become very ill due to the loss of Cosette—they find him already on his deathbed. Jean Valjean ultimately finds his final resting place in a pauper's grave.

Of course, this was just a rough retelling of events—the original is divided into three books and comprises about 600 pages, depending on the edition. The novel belongs to the Romantic era and reflects Hugo's personal interest in the French Revolution. Its detailed depiction of the difficult conditions of the lower class continues to distinguish it to this day.

Comentarios