The True Story of "Moby Dick"

- lillithpatzer

- Oct 15, 2024

- 9 min read

Imagine you live in early nineteenth-century America. You wake up in the morning. It’s still dark, so you turn up the oil lamp beside your bed, wash your face with a bit of soap, and get dressed. You spoon the leftovers from last night’s dinner: a vegetable soup. As you do, you glance at the faded landscape painting on the wall opposite you. Finally, you slip into your leather shoes, polishing them with some conditioner before putting on your captain's hat, leaving the house, and slamming the door shut behind you.

Smoking a cigar, you head toward the bustling harbor, where several ships are already being loaded. The sun begins to rise, and you walk purposefully toward a ship that is about 28 meters long, 8 meters wide, and 5 meters deep: the Essex.

Your goal – to catch a whale.

Whaling 101

All the items you interacted with before leaving the house (lamp oil, soap, soup, paint [on the canvas] and shoe polish) had something in common: they were all made from whale products. Therefore, in the early 19th century, before the discovery of petroleum, there was a particular focus on sperm whales. Their heads contain a lot of spermaceti, a waxy, oily substance. When a whale was caught and killed, the oil was extracted through the blowhole. The whale's blubber was usually boiled or beaten to extract the so-called whale oil. To facilitate this process at sea, whaling boats were often equipped with brick furnaces. Whale products played a significant role, especially during the Industrial Revolution and World War I. Whale oil was used as lubricant in factories, while whale oil was needed to produce nitroglycerin, or explosives.

How's it looking today?

I'm an animal enthusiast, so of course we're gonna talk about the wale-walfare now for a sec.

Because whales are particularly social and intelligent animals, whaling is no longer practiced in most countries. Today, we are able to produce such resources synthetically or have found "whale-friendly" alternatives, like petroleum. Officially, only Norway, Iceland, and Japan still hunt these gentle creatures, the latter claiming to do so solely for "scientific purposes." This is also due to the fact that excessive whaling has led to a rapid decline in the populations of certain whale species, such as the sperm whale, which are now partially protected.

Thanks for coming to my Ted-Talk. Now let's get back to the fishermen.

The Journey of the Essex

Back then, there was less restraint regarding whaling, as was the case with the 21-member crew of the Essex. The ship was commanded by Captain George Pollard Jr., who chose Owen Chase as his first mate. Chase brought his nephew, Owen Coffin, aboard. The position of second mate was filled by Joy. The ship's boys, Hendricks and the just 14-year-old Thomas Nickerson, were also set to play a role in the unfolding drama.

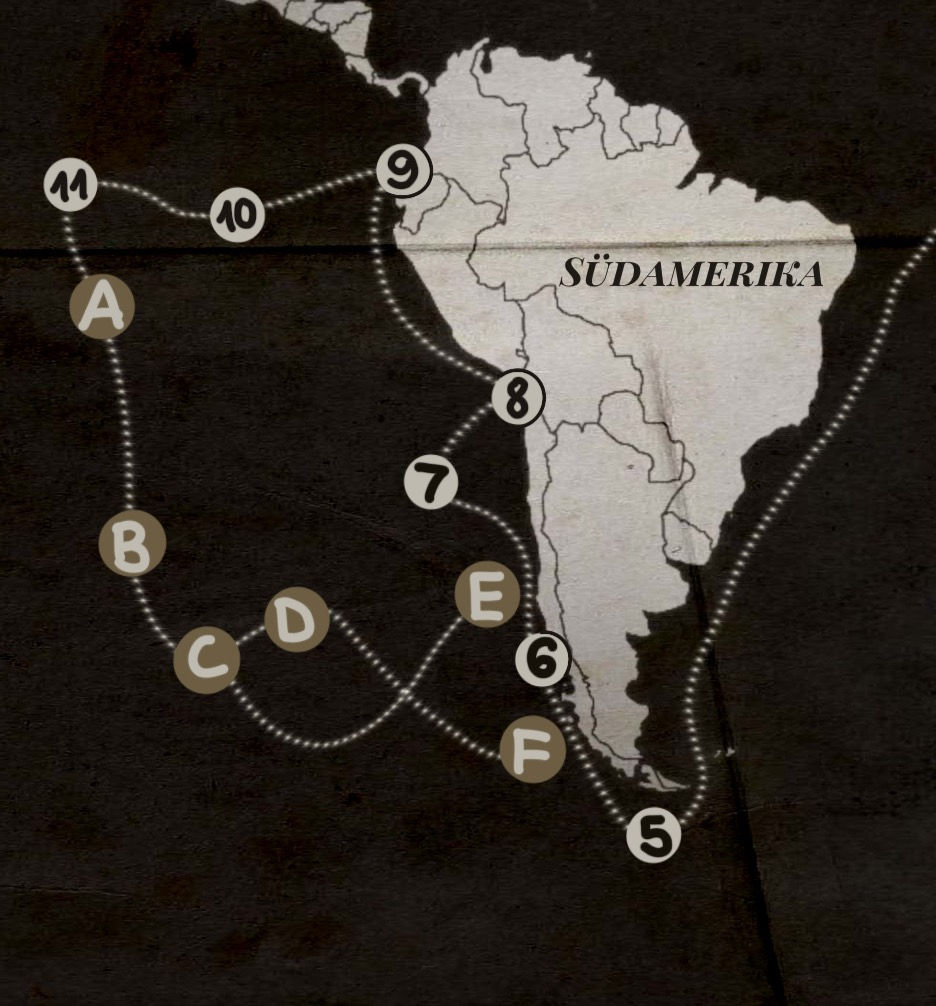

.On the morning of August 12, 1819, the Essex set sail (1) toward Africa. The winds there made it easier to reach the southern tip of America. After just three days at sea, the ship (2) capsized due to a violent gust of wind but quickly righted itself. However, the ship sustained damage, and two of the five whaleboats were rendered unusable due to the tilt. Captain Pollard's crew attempted to replace the missing boats during a stop in the Azores (3), as they were essential for whaling. (The crew would set out to sea on the roughly 8-meter-long whaleboats as soon as a whale was spotted and fire harpoons at it, leading to its eventual demise from internal bleeding.) Instead of getting replacement boats, the men stocked up on provisions during this stop.

At least one whaleboat was added to the crew during the next stop at Cape Verde (4), the westernmost point of the African coast, bringing their total back to four out of five boats available for whaling.

By now, the Essex had been at sea for three months, and the long journey to the southern tip of America went smoothly, aided by the southeast trade winds. Along the way, the crew managed to fill about half of the barrels with whale oil.

As the year turned from 1819 to 1820, the ship rounded Cape Horn (5). Captain Pollard was optimistic about returning home with full barrels, as they were now heading toward the Pacific—the mating grounds of the sperm whales.

The crew continued northward, making two stops in present-day Chile (6) to restock their supplies. Shortly after, they achieved their next whale catch (7).

Not long after, they steered again toward the South American coast to replenish their stores in the province of Arica (8). They then continued northward, but no further catches were made. With the coastal waters depleted, the crew decided to venture further out into the Pacific, where they believed a much larger population of whales could be found. They made another stop in Atacames (9), where one of the men deserted before setting course for the Galapagos Islands (10). There, the 20 men loaded giant tortoises as provisions. It had taken nearly a year to sail from the southern tip of America back to the north. It was now October 1820. Although the whaling season was over, the crew sailed fully loaded and in high spirits into the open Pacific—a devastating decision, as would be revealed about a month later.

Attack of the Sperm Whale

On November 20, 1820, the crew was puttering on the open sea when one of the cabin boys spotted a pod of sperm whales. The whale groups could be recognized from a distance by the water spouts they occasionally shot into the air. The crew initiated their first hunting attempt on the pod, but one of the whales launched a whaleboat into the air, prompting the crew to retreat for the time being.

The next morning, the remaining three boats were lowered again. Only Thomas Nickerson remained aboard the main ship as the helmsman. However, complications arose when a harpooned whale rammed Owen Chase's whaleboat, forcing him to paddle back to the Essex to temporarily patch up the damage with sailcloth.

On the way back, the men were alarmed to find that their ship had tilted sharply to the side for no apparent reason. Upon reaching the whaling ship, Chase and his crew attempted to cut the masts to lose the leverage, hoping the ship could right itself.

While working, Chase spotted a massive whale in the water. However, it appeared calm, so he paid it no further attention. No one noticed that the whale dove beneath the surface and reemerged about 30 meters in front of the Essex. At incredible speed, it shot toward the ship out of nowhere and rammed the whaler with its monstrous head, before Nickerson had the chance to react to Chase's command and steer away. The whale then swam alongside the Essex for a few minutes as if dazed. Suddenly, it attacked the bow of the ship. Then it dove beneath the surface and moved about 100 meters away, only to once again charge at the bow—this time with more momentum. The massive impact shattered the planks, and water began to flood in. The Essex started to sink. The whale disappeared.

As the ship went down, the crew quickly outfitted their whaleboats, which were designed for agility and speed, with materials from the Essex to turn them into seaworthy sailing boats, loading them with nearly 800 liters of fresh water and 300 kilograms of ship's biscuit. In the meantime, they also salvaged nautical manuals and tools such as charts, a telescope, and a compass, finally splitting into the three small boats, each led by Captain Pollard, Chase, and the second mate Joy.

On November 22, a Wednesday afternoon, the crew turned their backs on the wreck for good.

Odyssey in the Pacific

Now they faced an uncomfortable question: Where should they sail? A wrong decision could determine the life and death of twenty people. Captain Pollard suggested allowing themselves to be carried by the prevailing winds toward Hawaii; however, both helmsmen vetoed this idea, fearing they would fall into the hands of "cannibals" who still lived in New Guinea. Instead, their plan was to row against the wind southeast and then let themselves be carried eastward to the coast by the frequently shifting winds of the temperate zone. Pollard agreed, and the crew began their misadventure.

The Pacific was unpredictable; stormy waves alternated with calm waters and vice versa. However, the storms caused the ship's biscuit to become damp and rancid. Pollard's ship was also attacked by an orca but sustained no damage. The crew was continually pushed southwest and reached Henderson Island a month later (B). There, they found not only crabs, fish, birds, and other fresh meat but also a freshwater spring—a blessing for the hungry men.

After about a week, the supplies on the island were depleted; they had simply "eaten Henderson dry." Three crew members decided to stay behind when the remaining seventeen set sail again on December 27. This turned out to be a wise decision, as Seth Weeks, William Wright, and Thomas Chapple were rescued by the merchant ship "Surrey" on April 5.

Chase's boat lost contact with the other two boats on January 12 (C). Although Owen Chase, Thomas Nickerson, and Benjamin Lawrence were rescued by the "Indian" near a group of islands belonging to Chile (Juan Fernández Islands) on February 18, 1821 (E), the price of survival was high; they had to consume their starved comrades to avoid the same fate.

The remaining two boats lost sight of each other about two weeks later as well. Joy, the leader of one boat, died on January 10, which is why the cabin boy Hendrick took command. It is known that Joy received a Christian sea burial, but what happened after contact between the boats was lost remains unknown. It can be assumed that none from Joy’s or Hendrick's boat survived the ordeal in the Pacific. Considering the scene that unfolded on Pollard’s boat, perhaps that was a more merciful fate.

In February, the first to die of hunger on Pollard’s boat passed away, and like Joy, they were buried according to maritime tradition. As hunger began to drive the others to madness, they drew lots to decide who would die to provide food for the others. It fell upon the 17-year-old nephew of the captain, Owen Coffin. He accepted his fate and allowed himself to be shot without resistance. However, this sacrifice was not enough, and more men died until finally only Captain Pollard and sailor Charles Ramsdell clung to life—and the remains of their comrades.

On February 23, they were rescued by the "Dauphin." For the crew of the ship, also a whaler, it was not a pleasant sight;

"Their skin covered with soars, the castaways gnawed at the bones of their dead comrades with hollow-cheeked faces. Even when rescuers rushed to their aid, they refused to let go of their gruesome meal."

A total of eight out of twenty men survived the odyssey of 6,483 kilometers. Of the remaining twelve, seven were eaten, three were buried at sea, and two went missing.

Since both Thomas Nickerson and Owen Chase survived and kept meticulous records during the entire journey, as well as documenting their memories afterward, which they later published, it is still possible to reconstruct the course of the Essex and subsequently the whaleboats. Despite this traumatic experience, the survivors had to continue with their daily lives; Nickerson worked as a hotel employee in Nantucket, while both Pollard and Chase continued their work as whalers.

The Essex & Moby Dick

Owen Chase's son also entered the whaling business at an early age. At the age of 16, Chase Junior met the young Herman Melville on a whaling ship, who was also interested in whaling and showed him his father's book. Chase had published his experiences under the title "Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex, of Nantucket" (alternatively "The Wreck of the Whaleship Essex," or in German editions "Der Untergang der Essex" or "Tage des Grauens und der Verzweiflung"). Melville, who at that time was making ends meet as a land surveyor and teacher but already had literary ambitions, was inspired by Chase's book. Some time later, he also met Owen Chase himself. As only a few copies of the book were printed, Melville didn’t obtain a copy until 1850 through his father-in-law, who lived in Nantucket.

With the words "Call me Ishmael," Melville began his soon-to-be classic "Moby-Dick," in which the vengeful Captain Ahab hunts the white whale that had bitten off his leg. Like Chase, the narrator tells the story from the perspective of a crew member on a whaling ship, describing the perils of the sea and the attack of a seemingly aggressive whale.

Thus, the tragic sinking of the Essex became the inspiration for the dramatic ending of Moby-Dick.

For me personally, one question remains unanswered: why would a whale attack a ship out of the blue instead of fleeing? I consider the description of a whale as "vengeful" to be a manifestation of the whalers' guilty conscience. Whales typically attack with their jaws or massive tails; while Chase reported that the whale "snapped its jaws and slammed its tail on the sea in a frenzy of rage," it ultimately rammed the ship with its head—an unusual behavior for an attack.

It's important to remember that Chase, Pollard, and the crew were in the process of repairing the lifeboat when the whale "attacked." Knowing that hammering sounds resemble the acoustic signals whales use to communicate with each other, and considering that the Essex was in the whales' mating grounds, a different picture emerges. The sperm whale might have seen the ship as a potential mate or rival and acted without malicious intent. After all, sharks were associated with malicious, aggressive behavior toward humans for years until it was discovered that a surfer on a surfboard can easily be mistaken for a seal, their natural prey.

We should stop projecting human emotions like anger or revenge onto wild animals, where they are simply acting out their natural behavior. Humans are the unwelcome intruders invading the animals' habitat, not the other way around. Shouldn't the whale, even if it acted with destructive intent, be allowed to defend its pod, territory, and ultimately its life? After all, we humans would do the same.

Comments