Since Since Dan Brown's "The Da Vinci Code," a wide audience has become fascinated with various theories about mysterious messages hidden in the most famous artworks of all time. In the bestseller, the protagonist Robert Langdon not only explains the feminist background of the Mona Lisa, but he also claims to have uncovered the secret of the Holy Grail. Whether one gets lost in speculation or dismisses the topic as a "conspiracy theory," hypotheses of this kind are certainly intriguing. Here are five famous artworks that (allegedly) hide secret messages.Dan Brown's "The Da Vinci Code," a wide audience has become fascinated with various theories about mysterious messages hidden in the most famous artworks of all time. In the bestseller, the protagonist Robert Langdon not only explains the feminist background of the Mona Lisa, but he also claims to have uncovered the secret of the Holy Grail. Whether one gets lost in speculation or dismisses the topic as a "conspiracy theory," hypotheses of this kind are certainly intriguing. Here are five famous artworks that (allegedly) hide secret messages.

No. 1 The "Mona Lisa"

The "Joconde," as the French call it, is likely known even to the greatest art haters. Da Vinci originally named it "La Gioconda," which translates to "the Joyful." Alternatively, the painting was also known as "Madonna/Monna Lisa," meaning "Lady Lisa," from which the German name derives. While it hung in Napoleon's bedroom about 200 years ago, today it can be admired by everyone in the Louvre.

Despite its fame, it remains unclear who the subject of the painting was. One theory suggests that it depicts the Florentine Lisa del Giocondo. Others speculate that it could be a prostitute. Allegedly, the records of a student of Da Vinci explicitly name the model of the Mona Lisa as Isabella Gualandi, who is said to have worked in that profession. The second, less concrete "evidence" is the absence of facial hair on the lady, such as eyebrows and eyelashes, as this was an indication of prostitution at that time. On the other hand, the face of the Mona Lisa does tend toward a rather androgynous appearance, and Da Vinci may have found her too masculine with facial hair.

Due to the hand position of the Joconde, there has also been speculation about whether she might have been pregnant. The fascinating smile is said to have arisen from toothlessness. She is also rumored to have had a tumor in her right eye. However, these speculations should only be mentioned in passing.

The "Layer Amplification Method" (short L.A.M.) uses 13 high-quality images from a multi-spectral camera to generate 1,650 images through mathematical algorithms based on the laws of light and materials. This massive amount of data makes it possible to virtually differentiate various color layers that are not visible to the naked eye and often go undetected by X-rays.

This method allows, among other things, for the removal of the yellow tint that a painting inevitably acquires over time. Additionally, it enables the identification of specific pigments, which are then matched by software. This process can revive the original colors of a work of art.

Moreover, the L.A.M. has uncovered mysterious numbers and letters within the painting. The initials of the artist (L, V) can be seen in her right eye, while the letters C and E appear in her left eye. Additionally, the number 72 is said to be depicted on her nose, and the number 149 at the bottom of the painting.

What these numbers and letters mean has yet to be deciphered. Whether the mystery of the smiling lady will be solved in the future or if Da Vinci took this knowledge to his grave remains to be seen.

No. 2 Childish Mozart

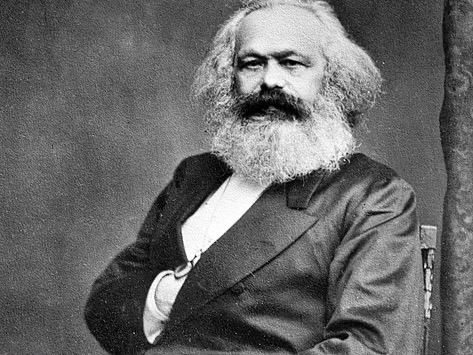

It’s no secret that some of the most influential figures in history were Freemasons. Not only Goethe and Lessing, but also George Washington, the first President of the United States, the famous military leader Napoleon Bonaparte, King Frederick II (known as Frederick the Great) of Prussia, Karl Marx, and the Austrian composer and child prodigy Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart are said to have belonged to this myth-laden secret society.

While Freemasons are organized into independent subgroups known as "lodges," the fundamental ideals that are to be lived out in daily life and are largely pursued by all lodges include freedom, equality, brotherhood, tolerance, and humanity.

Freemasonry, also known as the Royal Art, sees itself as an ethical union of free individuals (historically only men) with the belief that continuous self-improvement leads to self-awareness and more humane behavior.

How does one recognize like-minded individuals as a member of a secret organization?

The answer: Symbols and gestures that are openly displayed but known only to the initiated. Since the persecution of Christians at the beginning of the first century AD, certain signs have been established to express a person's mindset, often in the form of a tattoo. (Certainly, earlier cultures developed similar "codes," but since Freemasonry is a European-influenced organization, I will set those aside. If you're interested in the symbolism of persecuted Christians, you can find a brief excursion in my interpretation of the painting "Salome" by Lovis Corinth.)

Here are images of the aforementioned representatives of Freemasonry. Do you notice a pattern?

Napoleon, in particular, was often depicted in this pose, leading to numerous speculations. Some claimed he had a painful stomach ulcer or breast cancer, a skin disease, or a deformed hand. Others suggested he was winding his watch or secretly smelling a scent pouch hidden in his waistcoat; perhaps the painter simply didn’t like to paint hands.

However, none of these explanations seem plausible. Furthermore, this enigmatic pose is not limited to Bonaparte, as it has been employed by many others, as just exemplified. A Masonic interpretation of the pose would look something like this:

The heart represents our feelings and thus what we are and what we believe in. The hand, as a tool, symbolizes our actions. Therefore, someone who poses in this way is essentially saying: "This is what I believe in and the interests that guide my actions."

So far, so good.

In the context of Freemasonry, adult men (and possibly women) are expected to engage, while children should remain innocent and not be burdened with "adult matters."

This raises questions about the image of the child prodigy Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. At the tender age of 7, young Mozart posed in the "typically Masonic" stance. Given that a child, especially at that time, would likely not have been allowed the freedom to position themselves, it is reasonable to assume that he was arranged by his father or the responsible painter, Pietro Antonio Lorenzoni. However, "Wolferl" (a nickname for Mozart) later introduced his father, Leopold Mozart, to Freemasonry as an adult. Additionally, there are no known connections of the painter in this direction. Could it be that young Amadé chose this pose for himself?

Father Mozart recognized his son's talent early on, teaching both him and his daughter Maria Anna to play the piano and violin, as well as to compose, starting at the age of four. In 1762, Mozart began his first performances, and a year later, the painting of the young boy was created.

In 1764, Mozart composed his first significant work (KV 1: Menuett in G major with a Menuett in C major as a trio).

One could argue that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was forced to grow up early due to the circumstances of his childhood. However, I still find it very unlikely that a seven-year-old would join a secret society.

Another perspective is presented in an article from the website Zeit und Geist, from which I draw most of my information for this point. The article references statements by Prof. Dr. Uwe Flecken in the "Handbuch der politischen Ikonographie." In two volumes, 97 recognized experts in art history discuss over 100 political image strategies, including the so-called "Napoleon gesture." Flecken addresses the "hand in the waistcoat," as listed in the table of contents, explaining that this pose has existed since the 3rd century BC. The Greek orator Aeschines regarded gesturing with hands while speaking as impolite, which is why he concealed at least one hand in his toga. This created an ancient ideal that experienced a resurgence, particularly in the 18th century. Since then, the gesture has been associated with modesty, intelligence, authority, and leadership. It’s no surprise that people in positions of power, despite various ideologies, have adopted this pose. Above all, however, Napoleon continues to be associated with it. Given that the exit of the French ruler was anything but glorious, the well-known "Napoleon gesture" and its significance have faded from memory.

While it is confirmed that Mozart was a Freemason in his later years and incorporated such ideals into his famous opera "The Magic Flute," it is clear to most that the 7-year-old was not a member of a secret lodge, even though that would be a much more sensational story.

No. 3 "The Last Supper"

It is likely due to da Vinci's genius that the Italian Renaissance painter appears twice on this short list.

In school, we were taught that da Vinci was a universal genius, well-versed in all areas of art as well as the sciences. "The Last Supper," particularly the suspected message within it, supports this claim.

Speculation about a musical message hidden in the religious painting had been ongoing for some time before Giovanni Maria Pala addressed the rumors in 2003. The musician (and computer technician) overlaid musical staves on the painting and discovered that the loaves of bread and the hands of the depicted figures could indeed represent musical notes.

When he read the supposed melody from left to right, according to European standards, it made no sense. However, since Leonardo often wrote in mirror writing, from right to left, Pala read the notes backward—and behold, a melody emerged.

The musician recognizes the sequence of notes as a "Hymn to God." He subsequently explained that this melody is best played on an organ—the number one instrument for religious compositions. Pala interprets the melody as a sort of requiem, which aims to musically underscore the suffering of Jesus.

Following this, the Oxford graduate published the book "La Musica Celata" (The Hidden Music) in 2007, where he shared his findings with the world. Since Leonardo da Vinci also built instruments and had previously concealed musical puzzles in his writings that needed to be read from right to left, experts, including art historian Alessandro Vezzosi, who specializes in da Vinci, find Pala's discovery plausible. However, he simultaneously warns against reading too much into certain artworks, as the human mind is constantly seeking patterns.

No. 4 "Coffee Terrace in the Evening"

Particularly the loss of his right ear and the extraordinary color palette of his later works made Vincent van Gogh one of the most famous painters of (Post-)Impressionism. The painting "Café Terrace at Night" is among his most renowned works, alongside "Starry Night" and his "Self-Portrait." Today, "Café Terrace at Night" is exhibited in the Van Gogh Gallery of the Kröller-Müller Museum in the painter's birthplace.

One theory suggests that the figures on the terrace represent Jesus and his disciples.

The seated individuals are said to be the eleven faithful disciples, while the shadowy figure seemingly exiting through the front left door is interpreted as Judas, who betrayed Jesus. The standing figure, likely a waiter, is identified as Jesus. The lantern positioned slightly above and to the left of his head is seen as a halo. The white clothing, possibly an apron, worn by this supposed Jesus symbolizes virtue and purity due to its color.

I should note that I see only 11, rather than 12 "disciples" on the terrace. If we include the person on the sidewalk to the right, the group would be complete. One argument for including this figure is his proximity to the tables, which, although located beside the terrace, clearly belong to the café. Whether this figure should be given a special interpretive significance due to his unique positioning in the painting is questionable.

The lighting on the terrace might further represent the religious enlightenment that Jesus and his disciples experienced. This would explain why the betrayer Judas is depicted merely as a shadow, despite being positioned closer to the front of the image than the other figures, who are rendered in greater detail due to the illumination.

Additionally, the people who do not belong to the Christian faith and whom Jesus preaches to literally "walk in darkness."

As a final argument for a Christian motif, the scene itself echoes the famous depiction of Jesus and his 12 apostles by da Vinci in "The Last Supper." What better setting for a modern interpretation of this Renaissance artwork than a café or restaurant, where people primarily gather to eat together? The title of the painting itself offers the first clue. Although many of van Gogh's works depict night scenes and stars adorn the night sky here, he chose "evening" for the title.

On one hand, "evening" could allude to "The Last Supper"; on the other, it represents the end of a day, or in a religious context, the end of Christ's life.

It sounds like a neat hypothesis, but without supporting facts, it remains just that: a logical construct that cannot be proven.

The question then is to what extent religion played a role in van Gogh's life.

The Bible states that Christ is the light of the world, offering strength to the weary and burdened in life's darkness. The waiter also distributes "strength" in the form of nourishment through the offered meals.

As the son of a pastor, van Gogh was not only familiar with the Holy Scriptures but seemed destined for a religious life. After becoming disenchanted with the art trade, he attempted to become a pastor but failed. He dropped out of both his theology studies and a training program focused on the practical aspects of preaching.

The Evangelist Committee described van Gogh as highly committed (at one point, he gave away his most valuable possessions to live as poor as the early Christians), but they deemed him unsuitable as a preacher because he lacked "the gift of the word." In response to this rejection, van Gogh criticized "the conventions and prejudices of the evangelists" but subsequently dedicated himself to painting.

"I have delved too deeply into the cards of Christianity,"

van Gogh said later. The religion he learned in his childhood home increasingly seemed outdated and conservative to him. He yearned for a "modern religion." He found this idea echoed in Victor Hugo's writings, particularly the quote, "Religions pass away, God remains." This strengthened his vision of a new, transcendent religion where faith exists free from any conventions. He saw God manifested in human creativity, which made his worship more vitalistic. This perspective also explains why van Gogh later attributed a monastic significance to his studio and led a monk-like life as a painter. During his period of religious transformation, he attended church services less frequently, eventually refusing to accompany his parents to the Christmas service, which greatly displeased the strict evangelical couple. Shortly thereafter, he moved out of the family home.

He was particularly fascinated by the works "Scenes of a Clerical Life" (1859) and "Janet's Repentance" (1877) by G. Eliot (actually Mary Anne Evans). In a conversation with his brother Theo, he referred to the latter and expressed a "desire for religion among the common people in the great cities."

Van Gogh painted the scene in Arles, one of the oldest cities in France, showcasing the connection he sought between the city, the common people, and religion, assuming a religious background in the painting.

During his time in France, he also mentioned to Theo a "urge for [...] religion." Nevertheless, his goal was not to explicitly depict biblical scenes. Instead, he aimed to create an "atmosphere like at Christmas" and capture the religious feelings of a moment. Examples of this can be found in lesser-known works by van Gogh that portray praying figures or individuals reading the Bible.

"I want to paint men and women with that certain eternal quality, for which the halo was once a symbol, and which we try to convey through the glow, the trembling, and the vibration of our colors."

Perhaps this drive for new, modern religious ideas led him to create a reinterpretation of "The Last Supper." I believe that "Café Terrace at Night" is such an interpretation—one that aligns with van Gogh's eccentric, dreamy worldview, aiming to dissolve conservative notions while primarily reflecting his views on God and the world.

Most biographical information and all quotes used come from the article "Van Gogh and Religious Expression" by Jan Kohls in the "Journal for Theology and Church," Vol. 102, No. 4 from the year 2005.

No. 5 "The Swing"

When Jean-Honoré Fragonard's painting "The Swing" was first published, it faced significant criticism for its frivolity. This led, among other things, to the artist's influence being largely ignored for the first 50 to 100 years after his death. In performances by contemporary French artists, he wasn't even mentioned. Nonetheless, especially "The Happy Accidents of the Swing" (the original title of the oil painting) ultimately earned Fragonard his present-day fame.

The original client initially commissioned the painter Gabriel François Doyen to depict his mistress swinging on a swing. However, finding the scene too obscene, Doyen passed the commission on to Fragonard.

While the painting appears dynamic and carefree, I wouldn’t describe it as "offensive" at first glance—unless one deliberately recognizes the context of the image.

The woman is depicted in a light pink dress, making her appear like a flower in the otherwise blue-green garden, especially when combined with the voluminous skirts. The fact that the scene takes place in a garden is also significant. In pre-revolutionary France, beautifully designed gardens were considered romantic, private retreats, particularly for the upper class. The lavish garden of Marie Antoinette around Versailles, with its pavilions, lakes, and residences, is a well-known example.

The woman throws her right shoe towards the statue on the left edge of the painting. The small boy on the pedestal is a representation of Cupid, the god of love, often depicted as a small, winged child. The Greeks referred to him as "Eros," which is also the Greek word for the erotic type of love. Thus, this element is the first significant symbol of Fragonard's work.

Additionally, the raised foot opens the view for the man in the lower left corner to see under the woman's skirts. Since underwear was long considered "typically male" and only became standard female attire in the early 19th century, women wore only knee-length shifts and/or underskirts, along with knee-high stockings beneath their elaborate garments. No wonder the supposed lover looks a bit flushed.

Finally, the arrangement and posture of the figures may allude to a sexual act—where the woman is on top. She swings back and forth, while the man below stretches his "phallic" arm toward her open legs.

Overall, in my opinion, Fragonard's painting reflects the situation of French society just before the revolution—a France where the poor were starving while the nobility lived in luxury and extravagance—a France where it was not unusual to sit on a gold-embellished, velvet-upholstered swing while farmers went bankrupt. Hedonism was the order of the day, even if one would never admit it.

Comments